|

Donald G. Cook |

|

|||

| Rank, Service | ||||

Colonel O-6, U.S. Marine Corps |

||||

| Veteran of: | ||||

|

||||

| Tribute: | ||||

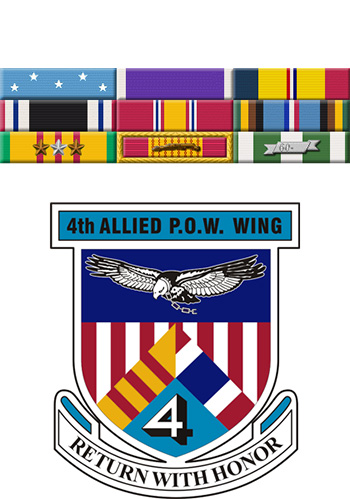

Donald Cook was born on August 9, 1934, in Brooklyn, New York. He entered the Officer Candidate Course with the U.S. Marine Corps on August 8, 1956, and was commissioned a 2d Lt at MCS Quantico, Virginia, on March 23, 1957. After attending the Basic School at MCS Quantico, Lt Cook served as a Communications Officer with the 1st Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California, from January 1958 to April 1960, followed by U.S. Army Language School at Monterey, California, from June 1960 to May 1961. Lt Cook then attended the U.S. Army Intelligence School at Fort Holabird, Maryland, from June to September 1961. His next assignment was as an Intelligence Team Leader and Plans Officer with Fleet Marine Force Pacific at MCB Camp H.M. Smith, Hawaii, from September 1961 to August 1964, followed by service as an advisor to the South Vietnamese military with the 3rd Marine Division from August 1964 until he was captured and taken as a Prisoner of War during the Battle of Binh Gia on December 31, 1964. He was reported to have died in captivity on December 8, 1967, but his remains have never been returned. Col Cook was officially listed as Missing in Action until declared dead on February 26, 1980. The guided missile destroyer USS Donald Cook (DDG-75) was named in his honor. Col Cook was the first and only Marine to be awarded the Medal of Honor for actions as a POW and he was the first Marine POW to have a U.S. Navy ship named in his honor. His Medal of Honor Citation reads: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while interned as a Prisoner of War by the Viet Cong in the Republic of Vietnam during the period 31 December 1964 to 8 December 1967. Despite the fact that by so doing he would bring about harsher treatment for himself, Colonel (then Captain) Cook established himself as the senior prisoner, even though in actuality he was not. Repeatedly assuming more than his share of responsibility for their health, Colonel Cook willingly and unselfishly put the interests of his comrades before that of his own well-being and, eventually, his life. Giving more needy men his medicine and drug allowance while constantly nursing them, he risked infection from contagious diseases while in a rapidly deteriorating state of health. This unselfish and exemplary conduct, coupled with his refusal to stray even the slightest from the Code of Conduct, earned him the deepest respect from not only his fellow prisoners, but his captors as well. Rather than negotiate for his own release or better treatment, he steadfastly frustrated attempts by the Viet Cong to break his indomitable spirit and passed this same resolve on to the men whose well-being he so closely associated himself. Knowing his refusals would prevent his release prior to the end of the war, and also knowing his chances for prolonged survival would be small in the event of continued refusal, he chose nevertheless to adhere to a Code of Conduct far above that which could be expected. His personal valor and exceptional spirit of loyalty in the face of almost certain death reflected the highest credit upon Colonel Cook, the Marine Corps, and the United States Naval Service. |

||||

|

||||